Introduction

Among the books that once belonged to Arthur Schopenhauer, including his Spanish books, we find handwritten annotations, reading marks and drawings (Hübscher 1968; Losada 2011). Most of the annotations are underlining, vertical lines in the margin, cross references, etc.

On this project

This project seeks to analyze Schopenhauer’s manuscript annotations in his Spanish books (interpretation), to encode them using TEI-XML (digital mark-up), and publish them digitally (diffusion).

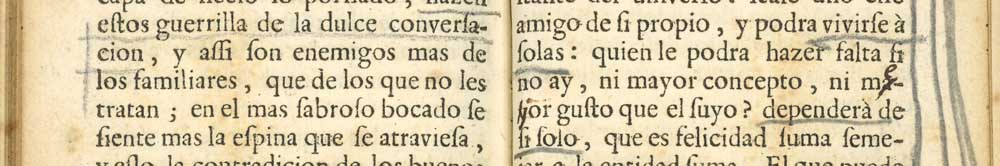

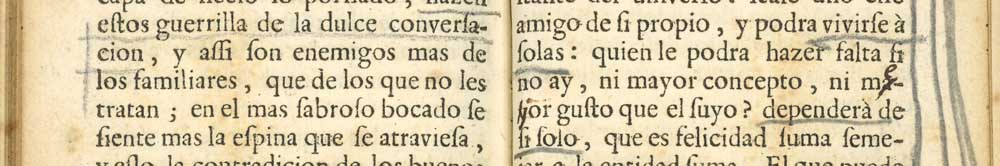

The first book we are working on, partially transcribed and encoded, and available online, is the Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (1647), in an edition from 1659, full marked with underlining, mostly in pencil, used by the philosopher for his German translation of Baltasar Gracián Das Handorakel und Kunst der Weltklugheit.

Schopenhauer’s library

Although Schopenhauer was not as a great book collector as a contemporary romantic writer like Ludwig Tieck, he was indeed an avid reader, who used books as a recipient for custom annotation and the library as a notepad: “Die ganze Weltliteratur weist keinen Schrifsteller von ähnlicher Bedeutung auf, der seine gesamte umfangreiche Bibliothek so wie Schopenhauer zu einem Archiv eigener Bekenntnisse ausgestaltet hätte" (Hübscher, 1968: XII)

Schopenhauer’s personal library had around 38 Spanish books. The Johann Christian Senckenberg University Library (Frankfurt am Main) in collaboration with the Schopenhauer-Archiv, where the personal library and literary remains from the german philosopher can be found, has digitized some of them: El Discreto (1665); Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes (1652); Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (1659); El político (1659); El Héroe (1659), but many books with personal marginalia are still not digitized: Examen de ingenios para las sciencias (1603), El café, ó la Comedia nueva (s.a.), Vida y hechos de Don Quijote de la Mancha (1719), Numancia (1811).

Author’s marginalia

We refer to a specific type of annotation within an author’s personal library: the author’s marginalia. The corpus of annotations and marks on books are in a few cases the focus of a critical edition, as part, for example, of the critical apparatus; they also are included in typical studies of author’s reception or textual genetics, but normally they are excluded in the textual scholarship. An author’s library rather belongs to the so called ‘grey canon’ (e.g. marginalia, reading notes, production notes) in contrast to ‘the black canon’ of the printed book (Hulle 2016: 115).

Given the recent impulse of the cultural turn, many of them has been recollected to examine the “potential value of readers’ notes for historical studies of reception and reader response” (Jackson 2001: 6). There are various formal similarities shared with, e.g., anonymous marks on medieval manuscripts, scholia or classical glosses of philological studies, books subject to censorship, marginalia scaenica, marks from a writer as editor of his own work during the process of reviewing (often object of textual genetics), but we are taking into consideration just the author’s marginalia. All marginalia types share, though, a common perspective: the reading process and the traces left in the text.

Digital Editions of marginalia

Very few are digitized and disseminated, due to the complexity of the editions; even for the new digital approach they present a challenge, because they are frequently linked to the context in which they appear, the materiality of the book. Only scanning the container (scans & metadata) does not facilitate their diffusion due to the lack of contextualization, although it helps to locate them.

A few institutions have undertaken major research projects for encoding and displaying annotations or scribblings of other authors’ printed works, such as, the digital project "Digitizing Walt Whitman's annotations and marginalia" — within the vast project The Walt Whitman Archive. Also in the United States we find Melville's Marginalia Online", which is a virtual archive of books owned and borrowed by Herman Melville. The project supplies links to digital copies of Melville’s books accompanied by bibliographical descriptions and documentary notes, as well as documentation and transcriptions of marginalia. In Europe, The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project has collected manuscripts and transcriptions of Samuel Beckett to facilitate the research within the methodology of genetic criticism. Marks and notes are exhaustively referenced in the digitized library, and in some cases some marked passages have been selectively transcribed. The project offers a unique opportunity to learn how Becket, who called himself “phrase-hunting” (Hulle and Nixon, 2013: XV-XVI) interacted with English, French, and Italian literature classics, showing that he was, as well as Arthur Schopenhauer, a great polyglot reader.